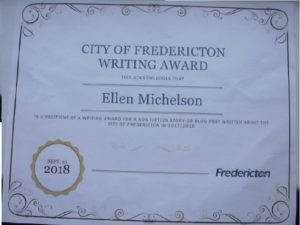

This short essay is one of the two pieces I wrote that were recognized in the contest described below it. Written not much more than a year ago, my essay was in a sense outdated as I created it. My memories of a proud event in the history of democracy, a Ukrainian election that was internationally recognized as successful, became juxtaposed, as I formulated them, with their opposite, the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Joy and pride have given way to misery and destruction, and challenges to democracy in Ukraine and elsewhere have grown more, not less, intense.

The Shimmer of Democracy

“Ya,” she said, unfolding a piece of paper, then “Ya,” again. Now and then she said “Yu,” but mostly she said “Ya.”

It was the evening of December 26, 2004. All of us from Canada had given up Christmas. More than five hundred of us were in Ukraine, where Orthodox Christmas was celebrated in January. We came as official election observers for the Orange Revolution’s second presidential election runoff, after the previous effort was declared fraudulent. The two candidates were Viktor Yanukovich and the nearly-assassinated Viktor Yushchenko. A handful of us were among those watching this woman standing at a table in a polling station as she unfolded ballots, one at a time. We knew our fellow observers were doing exactly what we were doing right then, all over Ukraine, seeing ballots being counted.

We had watched the tall, transparent ballot boxes sparkle as they caught the light when they were upended and the ballots inside them mounded onto the table in front of her. Those ballot boxes’ beauty delighted me. Their literal and figurative transparency was a beacon to the world.

As the woman read aloud the chosen candidate’s name on each of the first few ballots, a current of understanding went through all of us. It was already dark outside, and after each ballot was examined, they all had to be tallied, and then the totals reported in person to the district, then further, so all could be tallied nationally. When she suggested reciting just the first syllable of each candidate’s surname, we all nodded in full consensus. In English, both candidates’ surnames are usually written starting with “Y”. In Ukrainian, which uses the Cyrillic alphabet, “Yanukovich” starts with the character that looks like a reverse “R” but “Yushchenko” starts with the letter pronounced “iu.” Hearing and understanding the difference made my whole body quiver with pride.

We were in Crimea, the peninsula stretching into the Black Sea at the very south of Ukraine. Yushchenko was the national favourite, yet the other candidate, Yanukovich, was more popular in Crimea. Those of us from Canada had split into smaller groups for the day, each with a list of polling stations to visit. We were to report how election rules were followed. Both we and the Ukrainians knew the eyes of the world were on all of us.

At every stop we met both candidates’ representatives. The respect each showed to the others, and to us, impressed us. Individual polling stations had unique problems they solved in mutually agreed ways. For example, windows in one location made voter privacy challenging. Wooden frames had been hastily constructed and curtains hung.

Starting early that morning we’d visited a variety of polling stations at institutions, municipal offices, even a military base. Everyone we spoke with, mostly through interpreters, was forthcoming about telling and showing how they were meeting requirements. We observers agreed on the clear sense that the Ukrainians prioritized teamwork over support for a specific candidate. They were keen to further democracy, and to show the world exactly how they were doing so.

Years before, I’d volunteered in three or four Canadian election campaigns, and twice I’d sat in school gymnasiums watching ballots counted. A while later, I’d served as a volunteer English teacher in Ukraine, travelling around the country as much as I could. Never had I imagined combining these disparate experiences till they emboldened me to apply to serve as an election observer. Nor had I realized the extent of election observation around the world.

In Ukraine, members of our Canadian group met a few people, heard of others, who’d come as individuals to observe the election. Official observers like us must be invited by the host country. Unlike me, many members of our group had family ties to Ukraine. One member of our group had none, but had volunteered as an official observer in other countries and looked forward to volunteering elsewhere in the future.

I’d never before served as an election observer abroad, nor have I been lucky enough to serve again. A volunteer English teaching colleague, not from Canada, didn’t observe the Orange Revolution rerun. When she told me she’d been an official election observer in Ukraine years later, my first question was, “Did they still use those shimmering ballot boxes?” They did.

The whole procedure she described evoked the details of my experience. Waking up early on election day, visiting numerous polling stations, watching the count in one, following those bringing its results to a central location, observing how the information was transmitted further were not all the steps. Next her team assembled to discuss and compile its report, as did ours in 2004. Only when we had communicated our findings to our own leaders were we done.

The crunch against my back teeth as I bit into a cabbage-stuffed pastry, the sticky fizzy pleasure of swallowing red Crimean champagne are two of my many memories of delicious Ukrainian food and drink. On election day I must have eaten breakfast, no doubt found lunch, and someone likely shared snacks around the table as we worded our report, but my recall of consuming anything that day is nil. Before closing my hotel room curtains and collapsing under the bedcovers, I remember observing moonlight dapple over the Black Sea. A December dawn was due in several short hours. Every election observation, I realized, includes an almost twenty-four-hour non-stop stretch.

I had offered my presence, wishing to support democracy in Ukraine. Standing with my fellow Canadians as we watched ballots being unfolded, standing in the moonlight hours later suffused with both exhaustion and satisfaction, brought home to me how election observation furthers democracy worldwide. Canadians, I hope, will invite international election observers here and send our own elsewhere more often. Now, in 2022, Ukraine is fraught with bloody conflict. Some day, international election observers will be able to return. We will all be better for it.

No Comments »